(CNN) -- Rich Franklin used to spend his days teaching math to high school students. Today, he spends his evenings in an octagon-shaped cage grounding and pounding fighters into submission in front of thousands of screaming fans.

"I do love teaching and working with the students, but I can't imagine sitting at home on a Friday night grading math tests or sitting in a faculty meeting," he said at a news conference in Atlanta, Georgia.

Franklin is one of the new stars of a rapidly growing sport called Mixed Martial Arts.

Their fights are filling arenas and attracting large numbers of male television viewers between the ages of 18 and 49, according to the Ultimate Fighting Championship, a pioneering brand in the sport.

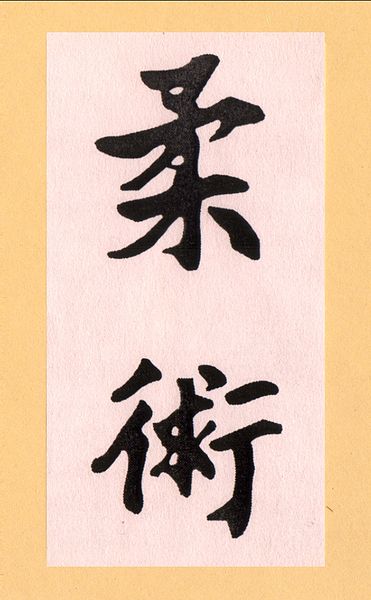

Unlike boxing, MMA fighters use a hybrid of techniques from wrestling, kickboxing, Brazilian Jiu Jitsu, and more.

Franklin began fighting professionally while still working as a teacher in Cincinnati, Ohio. He started playing football at a young age but didn't think he had the talent to play professionally, so he got into martial arts as a hobby after high school.

He trained through college, and on a dare, he entered an amateur fight and won. After his fourth year of teaching, he decided to gamble his job security to fight professionally full time.

"I'd rather be one of those guys who did and failed than wonder what could've, should've, would've been when I was 50," he said. Photo See photos from UFC 88 »

Having left the classroom behind, Franklin has achieved success as a fighter in the Ultimate Fighting Championship. He has held the Middleweight title, had commercial endorsements, and recently earned $100,000 with a victory at UFC 88.

Don't Miss

* UFC.com: Learn the rules

* SI.com: Lauzon ready to get back on track

* SI.com: Former UFC champ Tanner dies

Mixed martial arts has a controversial past. Critics view the sport as a bloody free-for-all akin to gratuitous Tough Man competitions, where average Joes with no formal training duke it out for prize money.

Rashad Evans, an undefeated UFC fighter, says that although the fights are full contact, it is not no-holds-barred brawling. "I wish people were more educated about the sport to know that it is not a Tough Man competition," he says.

Franklin views his fights as a physical chess match where fighters must know how to defend themselves against various fighting styles.

Fellow fighter Karo Parisyan, a judo specialist, agrees. He explains, "There are so many ways to win that you have to be constantly thinking. You make one mistake, and it's checkmate."

In a recent bout, although Franklin's face is bruised and bleeding, he waits patiently and releases a lightning-fast kick to his opponent's rib cage. The contact of his shin snaps like a bullwhip. His challenger falls to the floor of the cage, visibly in agony, and Franklin adds another win to his record.

Immediately after inflicting a TKO, Franklin rushes over to his opponent. He congratulates him and says, "Hats off to Matt, he fought a great fight."

Nate Marquardt fell in love with the sport at a young age. Today, at age 29, he already has had 40 professional fights. His fights, especially the losses, have taught him valuable lessons. "After you lose, a champion gets better, and losing was a blessing in disguise for me, because it helped me recognize my mistakes," he said.

Before his last fight, he had to drop 15 pounds, mostly water weight, from his already lean frame only days before the weigh-in. He said it wasn't easy, but he cut his intake of carbs and sodium, and he sat in a sauna, which did the trick.

Marquardt trains year round in pursuit of his dream to become the UFC's next Middleweight Champion. His success has afforded him the luxury to do so. He earned $56,000 from his last victory. When he doesn't have a fight coming up, he teaches at his gym in Aurora, Colorado, a couple of times a week.

He agrees that the lifestyle of a fighter gives him more flexibility to spend time with his immediate family than if he had a regular 9-to-5 job. He works his training schedule around spending time with his wife and caring for his 8-year-old daughter.

Marquardt may not have had his fighting opportunities if there hadn't been a vast overhaul in the sport. MMA was on the verge of extinction because of a political backlash in the late 1990s. One notable critic, Republican presidential nominee John McCain, once called it the equivalent to "human cockfighting."

Dana White, along with his partners Frank and Lorenzo Fertitta, purchased the fledgling Ultimate Fighting Championship for $2 million in 2001. White's goal was to establish the UFC as the Super Bowl of the sport. He helped legitimize it by establishing rules and promoting the fighters' skills instead of showcasing the brutality. Forbes estimates the company will make $250 million this year.

A UFC contract provides the potential for fighters to make a good living. Forrest Griffin, the UFC's current Light Heavyweight champ, earned $250,000 for a recent win in a main event. Sponsorships from sports drinks and apparel also help to supplement their income.

UFC fights have earned more money than concerts by such marquee artists as Elton John and Billy Joel, according to a UFC press kit. At times, the organization says, they have had more viewers than Monday Night Football and NASCAR. In Montreal, they brought in more than 21,000 people to an event, the largest live audience to witness MMA in North America to date.

advertisement

Televising fights has increased the number of fans embracing the sport. And at live events and autograph sessions, fans can mingle freely with their favorite fighters and take pictures with them.

"So many people are behind the sport now, and people are falling in love with it, so it's a matter of time before it's everywhere," says fighter Uriah Faber.

E-mail to a friend E-mail to a friend

Share this on:

Mixx Digg Facebook del.icio.us reddit StumbleUpon MySpace

| Mixx it | Share

No comments:

Post a Comment